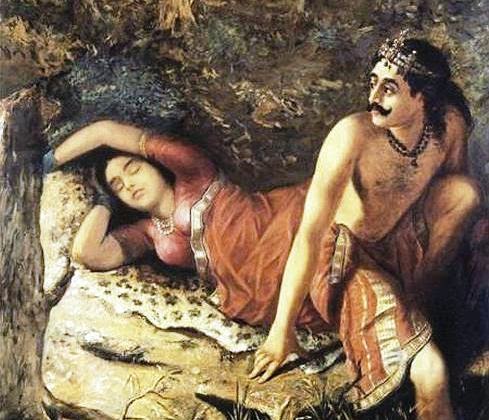

Nala and Damayanti

Yesterday I read Sunil Gangopadhyaya’s

version of the Nala-Damayanti story. This is a rather famous story in the

annals of Sanskrit literature originally found in the Mahābhārata, and I must surely have read it through before,

but in this case I found that it was unfamiliar and new. And it still requires

a bit of digestion, but on the whole it is a story of the glories of a woman’s

love. Once she has picked her man, she remains faithful until death, no matter

how lost her man becomes. Of course, by the intervention of the gods and the

power of her devotion to her husband, all is well in the end. And she even

becomes the power of compassion in her husband’s kingdom.

The story is, briefly, as follows. Nala is the king of

Nishadh. He has a half-brother Pushkar who has an unimportant role as a prince

in the kingdom and he hates Nala for having received their father’s blessings.

A swan acts as a go-between and brings Nala and Damayanti together at her

svayamvara. Since the swan has so completely sold the young princess on the qualities

of the king she has given her heart to him and will give it to no other. Four

gods – Indra, Varuna, Agni and Yama – decide to attend the svayamvara in order

to win her heart, and they devise a trick to defeat their chief competitor,

Nala.

When Damayanti tells the four gods she will take none other than Nala, they quickly transmogrify into exact replicas of Nala, with all his mannerisms and speech. "Now

choose," say the gods. Damayanti says to herself in a moment of meditation, perhaps directing her prayer to those very gods, “If

my vow and fidelity to Nala is true, then may I be given the subtlety of vision

to recognize which of these five exact replicas of Nala is the real one.” When

she looks again, she observes that one of the figures blinks and sweats and

shows other human features of which the gods are unsullied. So she picked

correctly. The gods were pleased with Damayanti and Nala blessed the couple.

But one minor god, Kali, felt that Damayanti had mocked the

authority of the gods by picking a human over them. So he decided to create

quarrel in the Nishadh kingdom. He went and made friendship with Pushkar and

found Nala’s weakness – gambling. With the help of Kali’s godly powers, Pushkar

was able to bring Nala to his knees through his gambling addiction, to the

point that he had to abandon the kingdom. The court ministers had already

advised Damayanti, who by this time already had two children, to return to her

parents’ kingdom of Vidarbha, because Nala had become so obsessed with the game

that he would cause their ruin, even gambling her away if she were not careful.

Of course, Damayanti is as beautiful as a goddess and coveted by all men, in

particular Pushkar.

As coincidence had it, Damayanti sees Nala on the road, for

he has already left on exile himself. She leaves the children in the care of

the charioteer and tells him to go on to Vidarbha, but that she would stay with

her husband in happiness or distress.

And so the dethroned and exiled king goes into the forest

where he and Damayanti undergo tribulations, nearly starving, always in danger

from the wild animals, without means or shelter. One day, Nala is hoping to

trap some geese. He removes his one cloth, his only tool, to use as a net. But

the clever goose nipped his cloth and flew off into the sky, leaving him

completely naked. Completely shamed before his wife, she gives him shelter

under her one cloth. Nala’s humiliation is complete. While Damayanti is asleep,

he tears her sari in two, uses one piece to cover himself – leaving her of

course inadequately covered, and runs away. He thinks, she will find the way to

Vidarbha, but I have nowhere I can go and hold my head up.

Another event takes place that is the work of the gods. As

Nala walks through the forest he hears someone call his name and asks to be

saved from a fire that surrounds. Nala enters the circle of flames and sees a

snake coiled and calling out to him. The snake tells him that he has been

cursed to be a snake and that he was told by Narada, who cursed him, that when

someone named Nala came by, he would release him from the curse. Nala picked

the snake up and took out of the fire, but rather than show gratitude, the

snake bit Nala – with only half his poison, but enough to disfigure Nala and

make him look like a lesser human of lower birth, dark skinned, stunted, with

inelegant features and uneven teeth. Nala has hit rock bottom. He goes looking for work, giving up any hope of returning to his family or his kingdom.

Meanwhile, Damayanti, half-naked, without defenses or protection, is lost in the forest, abandoned by her husband. She looks half-mad, her beauty clouded over by dust, her hair tangled clumped , one torn sari covering her nakedness and her eyes full of despair. She comes across a caravan and follows them and finally arrives in a town where she finds shelter and ultimately her way back home to Vidarbha. In all this time, however, she goes on wearing just the one cloth, vowing not to dress or decorate herself until she is reunited with her husband.

Damayanti's father sends out messengers to find news. She herself teaches them a song she has written, with questions that only Nala could possibly answer, "What manner of man abandons his wife, whom he has vowed to protect all her life, in the forest alone?"

Damayanti is finally able to recognize Nala for who he is by seeing his good qualities, even though he has been incognito in the disfigured form. Just as she was able to recognize him from amongst the gods, she was able to recognize him in his ugliness and loss of self confidence. Her wits and determination overcome Nala's shame and guilt and, most shamefully, his doubts about her fidelity.

So, the story ends happily, as it must. After finally being reunited with Damayanti and the children, Nala gets back his former beauty, his kingdom, and everyone lives happily ever after -- even Pushkar -- all thanks to the princess' pātivratya.

* * * * *

These are the kinds of stories that feminists love to hate

because woman is typecast in the shadow of the man rather than being something in her own right, like a man. Her role is circumscribed because on the one hand she is in need of a man's (or a man's world's) protection, yet she wants an independent role in the world that requires nothing of her other than her own abilities without accounting for the natural nurturing role that her biology conditions her to, in particular the extent to which men are formed in their identity by the women in their lives, mothers and wives.

Recently a woman said to me that everything I had proposed about Yugala Bhajan was really in pursuance of the "patriarchal agenda." Perhaps I was embellishing with a bit of mystical confabulation, but ultimately the purpose was still to objectify woman. After all, it serves a man more to divinize a woman who is the source of love, support, service, admiration and sexual enjoyment, than for a woman to divinize a man who is mortal, incapable of giving her everything she wants or needs, who demands total and unconditional support despite his failings, who seems to requires total surrender. Who is willing to accept the deal when children are no longer the issue? Does it not make better sense for the woman to strike out independently to seek out God rather than making the futile attempt to see the Divine in a fallible human?

Well, it is a myth, one of many such stories glorifying the sacred nature of the husband-wife relation. They find each other by Destiny and they believe in their Destiny. But times have changed and no one believes in the protecting arms of Dharma, or at least not one that is ready-made. Are there any women who can identify with Damayanti or are we to take her for a fool who gave the benefit of the doubt to her husband well beyond any logical expectations? Just another patriarchal story to bewilder women, bind them to their and to misguide her from her true freedom.

Well, it is a myth, one of many such stories glorifying the sacred nature of the husband-wife relation. They find each other by Destiny and they believe in their Destiny. But times have changed and no one believes in the protecting arms of Dharma, or at least not one that is ready-made. Are there any women who can identify with Damayanti or are we to take her for a fool who gave the benefit of the doubt to her husband well beyond any logical expectations? Just another patriarchal story to bewilder women, bind them to their and to misguide her from her true freedom.

Another way of looking it as that of a smart boss committing to a promising employee. Woman is guru to the man. The man's role in the external world is to protect and develop the inner world. The guru's faith in the disciple is the greatest act of compassion.

Comments