Yājñasenī (1): A living Sanskrit translation

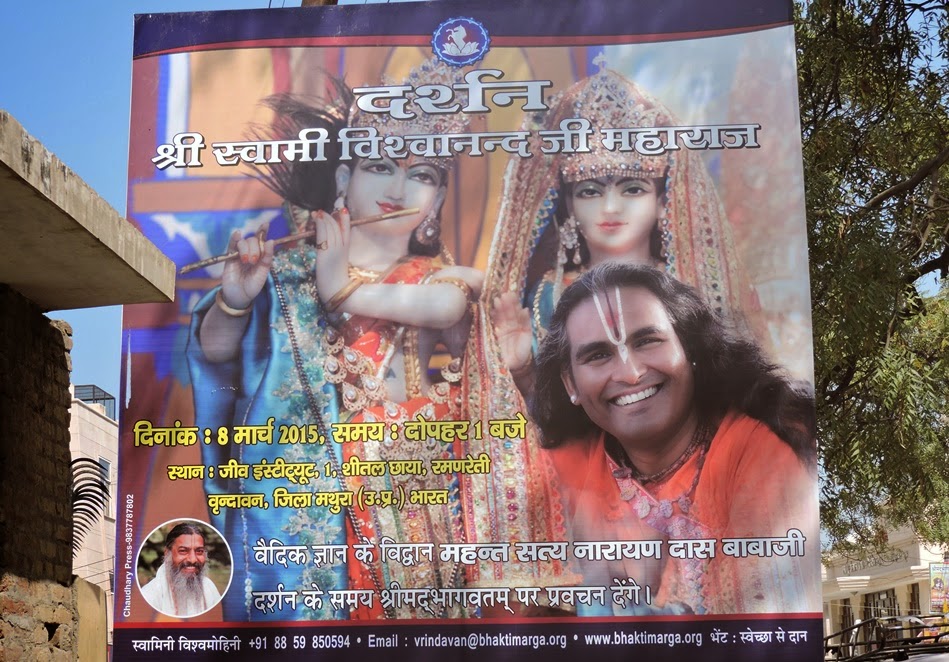

On my current literary distractions list is another book I picked up in Satya Narayan Dasji's basement. This is again a translation, but this time from Orissan into Sanskrit.

The author, Pratibha Ray, has won numerous awards and the original version of Yājñasenī (1984) was also a prize winner, winning the Moorti Devi Award,1991 and Sarala Award, 1990, and most recently, the prestigious Bharatiya Jnanapith award in 2011.

It was made into a popular Hindi teleseries and the famous film-actress Hemamalini also made a stage ballet adaptation of it. Hemamalini is currently involved in politics for the Bharatiya Janata Party, which perhaps sheds a little light on the underlying ethos of the author. And this is something that I will return to.

This translation was done by Bhagirathi Nanda and published by the Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan, which is an Indian government undertaking.

As the title indicates, Yājñasenī is the autobiography of Draupadi, the main female character in the Mahābhārata. In other words, it is the Mahābhārata, retold from Draupadi's point of view. Yājñasenī is one of Draupadi's many names, indicating that she was born from a sacrificial fire, which is interpreted to mean that she was born to serve dharma.

A great deal of Pratibha Ray's writing is based on women characters in the Puranic and epic traditions or from Indian history, and this is her magnum opus. In the Wikipedia article about Pratibha Ray, it is said that she attributes her orientation to her background in Vaishnavism as well as to the Gandhianism of her father, but she characterizes herself as a humanist.

First I want to say a little bit about the language, since this specific translation has had an interesting effect on me and a few words seem in order. It is a bit unusual to read a book that is translated into Sanskrit -- usually translations are done the other way round! -- but I think that this should definitely be encouraged. As a matter of fact, reading this has made me quite enthusiastic about Sanskrit.

It is written in a fairly straightforward but uncompromising classical language. It has a few personal idiosyncrasies, but on the whole it strikes me as an outstanding example of living expression in Sanskrit and I would recommend it, and furthermore hope that more and more of this type of translation will be done.

A few years ago I was approached by a businessman in Chennai who was looking for someone to head a Sanskrit college and someone had suggested my name. I did not take the offer too seriously, especially as the man was thinking in terms of teaching the traditional staples, with the career options mostly in astrology and priestly work. I suggested a translation school, a kind of modern-day Fort William for translating world literature classics into Sanskrit, start with Homer and Virgil and work up from there.

That is one way to enrich a language and bring it back to life. Sanskrit has tremendous potential as a medium of expression, but any talk of making Sanskrit a national language is futile if there is no living literature that is accessible, and where there is no cross fertilization with other cultures' ideas and rasas.

Now this might well sound heretical to some. For most modern Indians, Sanskrit has an association with the India of a distant and pretty much irrelevant past, and Sanskrit purists are also helping it win that reputation by consigning it exclusively to those areas of traditional knowledge that were mediated by it for millennia.

Yājñasenī could be considered a bit of a step in the right direction. It is not too foreign, as Oriya is an offspring of Sanskrit, and the themes of the book itself are steeped in the great epic, Mahābhārata. Nevertheless, the author's point of view is one that comes from the 20th century, from an India that is very different from the one of the Gupta period or whenever the Mahābhārata was finalized. The themes are well known, but the story as told can be viewed as commentary, like any retelling of a story always is. In that sense, it falls into a very real tradition of Sanskrit storytelling, much as even, say, Gopāla-campū retells the Tenth Canto of the Bhāgavata.

That makes it easy for the translator to adopt modes common to Sanskrit past such as descriptive passages that easily fall into recognizable cadences of the tradition -- with the names of flowers, birds, trees, place names and so on. In this book, however, hose familiar details of the language are not overplayed by a constant overlay of complex metaphors and alaṅkāra strings as in classical kāvya, rather they are woven into the fabric of the novel form, and it is the form itself that is modern and breathes life into the old girl, Saraswati.

And that is the major part of what makes me excited about this book.

This evening I was sitting with Swami Veda and found myself conversing with him in Sanskrit (writing on his tablet, since he is in silence and also hard of hearing!) just by the force of the natural flow of the language that is being absorbed into my brain. I have studied Sanskrit for forty years. I have attended Sanskrit Bharati workshops for spoken Sanskrit, and here in Rishikesh (in particular) I have had the association of several fluent Sanskrit speakers, but this book has come to me now, you could say, to do a prāṇa-pratiṣṭhā of all that accumulated book learning. It got me actually thinking in Sanskrit.

For the most part of late I have been working with Sanskrit philosophical works such as Yoga-sūtra and the Sandarbhas. It goes without saying that these works are written to present ideas to a well-defined audience in as succinct and stylized a manner as possible. They are specialized and difficult almost by definition.

In the past, I have also done a lot of reading in the areas of kāvya and purāṇas. Somewhere (I don't know if in this blog, but certainly in my introduction to Mystic Poetry) I have discussed quite defensively the criticisms of S.K. De of literary Sanskrit, especially that of our sampradāya. His view is that it is overly obtuse and even unnatural. But these are not just flaws of a late and decadent Sanskrit, they go back almost to the beginnings of the classical tradition, and much of what is written in the realm of Sanskrit kāvya was meant for a select group of connoisseurs, an elite in-group of pandits and scholars, even as it is now.

At the other extreme, a great deal of the purāṇas -- which were clearly meant as a means for vulgarization -- comes perilously close to doggerel. At the very least, let us say that the quality is uneven. But whether we talk of a literature intended for educated rasikas or for the common folk, none of it was written for anyone in the 21st century.

The kind of language S.K. De wanted to see was something that had developed in the way that Bengali did in the 19th century. Namely, a living prose tradition. If we look at acclaimed classical Sanskrit prose texts like the work of Bāṇabhaṭṭa, or Daśakumāracarita, or even the prose portions of the Bhāgavata, one can observe the same tendency to the elitist, ornate and artificial. parokṣa-vādā ṛṣayaḥ parokṣaṁ mama ca priyam. A prose that flows and carries you away, rather than challenging you at every step, is practically non-existent outside of some purāṇas. Works like Pañcatantra and Hitopadeśa are more accessible, but they are told like children's stories or parables and are a little too didactic to be truly evocative. All these works have their place, but limited in their ability to capture the mind, especially of a person who has the literary expectations of a modern person.

I am not an expert in understanding genres. But it seems that the modern novel emphasizes the weaving of many subtle strands that interplay in a complex fashion rather than the microcosmic format of the verse, which in Sanskrit has an express obligation to produce rasa every four lines. The sphoṭa theory of Indian linguistics can be seen on a macrocosmic level also, in the novel form, where the accumulation of small sphoṭas to come to a major climactic explosion of meaning at the end. But to do that it has to minimize the tendency to focus excessively on the micro manifestations of rasa and allow them to gradually build.

Certainly works like the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata owe their long lives to this kind of overall accumulation of complex meanings, but they have always been mediated through recitation accompanied by oral interpretation, which gives them their accessibility, but this is quite different from the reading culture.

[It is one of my observations about Indian culture how few people actually read novels in the vernaculars in India, even in Bengal where authors are national heroes. For instance, in the bus or metro, one rarely sees anyone with an open book, unlike in Canada, for example. Other than newspapers and religious texts, only a small percentage of the population has a literary bent. A general "library" culture is a desideratum of an "advanced" country.]

Of late, thoughts of "Krishna West" have been coloring much of my thought about my own engagement with India and its spiritual and cultural traditions, and before I go on discussing this specific book, I would like to discuss that a little in my next article.

I will leave out examples for today, but I expect to write another article or two on this book where I will have occasion to do so. Radhe Shyam.

The author, Pratibha Ray, has won numerous awards and the original version of Yājñasenī (1984) was also a prize winner, winning the Moorti Devi Award,1991 and Sarala Award, 1990, and most recently, the prestigious Bharatiya Jnanapith award in 2011.

It was made into a popular Hindi teleseries and the famous film-actress Hemamalini also made a stage ballet adaptation of it. Hemamalini is currently involved in politics for the Bharatiya Janata Party, which perhaps sheds a little light on the underlying ethos of the author. And this is something that I will return to.

|

| Hemamalini, the BJP candidate, waving to crowds. |

As the title indicates, Yājñasenī is the autobiography of Draupadi, the main female character in the Mahābhārata. In other words, it is the Mahābhārata, retold from Draupadi's point of view. Yājñasenī is one of Draupadi's many names, indicating that she was born from a sacrificial fire, which is interpreted to mean that she was born to serve dharma.

A great deal of Pratibha Ray's writing is based on women characters in the Puranic and epic traditions or from Indian history, and this is her magnum opus. In the Wikipedia article about Pratibha Ray, it is said that she attributes her orientation to her background in Vaishnavism as well as to the Gandhianism of her father, but she characterizes herself as a humanist.

I am a humanist; men and women have been created differently for the healthy functioning of society. The specialties women have been endowed with should be nurtured further. As a human being however woman is equal to man. (Pratibha Ray)This paragraph nicely summarizes the general purpose of the book. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that there is a distinct Hindu ethos along with a Vaishnava theology present in this story, which is certainly a matter of interest to me. And this is tied in to the theme of romantic love, taking on a rather unique form in that Draupadi has five husbands. And since the matrix of India and romantic love (madhura-rasa) is my principal area of interest to which I return again and again, I will, but in another post.

First I want to say a little bit about the language, since this specific translation has had an interesting effect on me and a few words seem in order. It is a bit unusual to read a book that is translated into Sanskrit -- usually translations are done the other way round! -- but I think that this should definitely be encouraged. As a matter of fact, reading this has made me quite enthusiastic about Sanskrit.

It is written in a fairly straightforward but uncompromising classical language. It has a few personal idiosyncrasies, but on the whole it strikes me as an outstanding example of living expression in Sanskrit and I would recommend it, and furthermore hope that more and more of this type of translation will be done.

A few years ago I was approached by a businessman in Chennai who was looking for someone to head a Sanskrit college and someone had suggested my name. I did not take the offer too seriously, especially as the man was thinking in terms of teaching the traditional staples, with the career options mostly in astrology and priestly work. I suggested a translation school, a kind of modern-day Fort William for translating world literature classics into Sanskrit, start with Homer and Virgil and work up from there.

That is one way to enrich a language and bring it back to life. Sanskrit has tremendous potential as a medium of expression, but any talk of making Sanskrit a national language is futile if there is no living literature that is accessible, and where there is no cross fertilization with other cultures' ideas and rasas.

Now this might well sound heretical to some. For most modern Indians, Sanskrit has an association with the India of a distant and pretty much irrelevant past, and Sanskrit purists are also helping it win that reputation by consigning it exclusively to those areas of traditional knowledge that were mediated by it for millennia.

Yājñasenī could be considered a bit of a step in the right direction. It is not too foreign, as Oriya is an offspring of Sanskrit, and the themes of the book itself are steeped in the great epic, Mahābhārata. Nevertheless, the author's point of view is one that comes from the 20th century, from an India that is very different from the one of the Gupta period or whenever the Mahābhārata was finalized. The themes are well known, but the story as told can be viewed as commentary, like any retelling of a story always is. In that sense, it falls into a very real tradition of Sanskrit storytelling, much as even, say, Gopāla-campū retells the Tenth Canto of the Bhāgavata.

That makes it easy for the translator to adopt modes common to Sanskrit past such as descriptive passages that easily fall into recognizable cadences of the tradition -- with the names of flowers, birds, trees, place names and so on. In this book, however, hose familiar details of the language are not overplayed by a constant overlay of complex metaphors and alaṅkāra strings as in classical kāvya, rather they are woven into the fabric of the novel form, and it is the form itself that is modern and breathes life into the old girl, Saraswati.

And that is the major part of what makes me excited about this book.

This evening I was sitting with Swami Veda and found myself conversing with him in Sanskrit (writing on his tablet, since he is in silence and also hard of hearing!) just by the force of the natural flow of the language that is being absorbed into my brain. I have studied Sanskrit for forty years. I have attended Sanskrit Bharati workshops for spoken Sanskrit, and here in Rishikesh (in particular) I have had the association of several fluent Sanskrit speakers, but this book has come to me now, you could say, to do a prāṇa-pratiṣṭhā of all that accumulated book learning. It got me actually thinking in Sanskrit.

For the most part of late I have been working with Sanskrit philosophical works such as Yoga-sūtra and the Sandarbhas. It goes without saying that these works are written to present ideas to a well-defined audience in as succinct and stylized a manner as possible. They are specialized and difficult almost by definition.

In the past, I have also done a lot of reading in the areas of kāvya and purāṇas. Somewhere (I don't know if in this blog, but certainly in my introduction to Mystic Poetry) I have discussed quite defensively the criticisms of S.K. De of literary Sanskrit, especially that of our sampradāya. His view is that it is overly obtuse and even unnatural. But these are not just flaws of a late and decadent Sanskrit, they go back almost to the beginnings of the classical tradition, and much of what is written in the realm of Sanskrit kāvya was meant for a select group of connoisseurs, an elite in-group of pandits and scholars, even as it is now.

At the other extreme, a great deal of the purāṇas -- which were clearly meant as a means for vulgarization -- comes perilously close to doggerel. At the very least, let us say that the quality is uneven. But whether we talk of a literature intended for educated rasikas or for the common folk, none of it was written for anyone in the 21st century.

The kind of language S.K. De wanted to see was something that had developed in the way that Bengali did in the 19th century. Namely, a living prose tradition. If we look at acclaimed classical Sanskrit prose texts like the work of Bāṇabhaṭṭa, or Daśakumāracarita, or even the prose portions of the Bhāgavata, one can observe the same tendency to the elitist, ornate and artificial. parokṣa-vādā ṛṣayaḥ parokṣaṁ mama ca priyam. A prose that flows and carries you away, rather than challenging you at every step, is practically non-existent outside of some purāṇas. Works like Pañcatantra and Hitopadeśa are more accessible, but they are told like children's stories or parables and are a little too didactic to be truly evocative. All these works have their place, but limited in their ability to capture the mind, especially of a person who has the literary expectations of a modern person.

I am not an expert in understanding genres. But it seems that the modern novel emphasizes the weaving of many subtle strands that interplay in a complex fashion rather than the microcosmic format of the verse, which in Sanskrit has an express obligation to produce rasa every four lines. The sphoṭa theory of Indian linguistics can be seen on a macrocosmic level also, in the novel form, where the accumulation of small sphoṭas to come to a major climactic explosion of meaning at the end. But to do that it has to minimize the tendency to focus excessively on the micro manifestations of rasa and allow them to gradually build.

Certainly works like the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata owe their long lives to this kind of overall accumulation of complex meanings, but they have always been mediated through recitation accompanied by oral interpretation, which gives them their accessibility, but this is quite different from the reading culture.

[It is one of my observations about Indian culture how few people actually read novels in the vernaculars in India, even in Bengal where authors are national heroes. For instance, in the bus or metro, one rarely sees anyone with an open book, unlike in Canada, for example. Other than newspapers and religious texts, only a small percentage of the population has a literary bent. A general "library" culture is a desideratum of an "advanced" country.]

Of late, thoughts of "Krishna West" have been coloring much of my thought about my own engagement with India and its spiritual and cultural traditions, and before I go on discussing this specific book, I would like to discuss that a little in my next article.

I will leave out examples for today, but I expect to write another article or two on this book where I will have occasion to do so. Radhe Shyam.

Comments